Piracetam as an Aid to Learning in Dyslexia

Preliminary Report

C. Wilsher1, G. Adkins2, and P. Manfield3

1 University of Aston, Birmingham, England

2 Birmingham, England

3 Good Hope Hospital, Sutton Coldfield, England

Abstract. Sixteen male dyslexic children were seen again when adults and matched with 14 student volunteers for a 21-day trial of piracetam. It was found, using a double-blind cross-over technique, that dyslexics significantly increased their verbal learning by 15.0% and students by 8.6% (over and above their placebo increase).

Key words: Dyslexia — Piracetam — Nootropyl — Verbal learning

Since Morgan’s (1896) original article on “word blindness” the exact definition of this complex medico-educational problem has been the subject of much controversy. However, for the purpose of this work dyslexics were chosen that adhered strictly to the definition given for specific developmental dyslexia agreed upon by a special international committee of the World Federation of Neurology (Critchley, 1970).

The exact neurophysiological nature of specific developmental dyslexia is not conclusive, but theories range from a maturational lag to that of impaired cerebral dominance (Orton, 1937). Recently the possibility of a biochemical imbalance within the tissue of the cerebral hemispheres has been suggested. Essentially the learning process depends upon memory and the complex integration of visual, auditory and kinaesthetic skills in terms of sound/symbol relationships, spelling and word patterns, sequence of letters, combination of letters, etc., requiring that information be retained and memorised (Thomson and Wilsher, 1978). The dyslexic individual has the inability to retain complex information over time (Miles and Wheeler, 1974) and therefore requires longer exposure to written language learning with considerable overteaching and overlearning. As recently as 1972, control studies using

methylphenidate (Ritalin) showed no benefit to the non-hyperkinetic poor reader (Gettelman-Klein, 1972). The idea of our study came from successful work which showed an increase in verbal learning ability of students given piracetam in a matched-pair double-blind trial (Dimond and Brouwers, 1976).

Materials and Methods

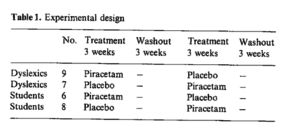

The experimental design had a double-blind cross-over system of random assigned matched groups [for intelligence (IQ)] with two dyslexic and two student groups. The experimental and washout periods were of 21 days and the dosage was two tablets of 800 mg piracetam or placebo TD (Table 1). The dyslexic groups were of 16 aduits who had previously been referred to Aston University Language Development Unit for literacy problems as children and diagnosed by criteria outlined by Thomson (1977). The subject’s ages ranged between 17 and 24 years and members of the dyslexic group were still having literacy problems. The 14 students were healthy volunteers, being average or good readers and matched for their IQ with the dyslexic group. All groups were given a battery of tests before commencement of the trial, including Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) (Wechsler, 1955), Vernon Reading Test (Vernon, 1938), Schonell Spelling Test (Schonell, 1942), Visual Sequential Memory in the Illinois Test Psycholinguistic Abilities (ITPA) (Kirk et al., 1969), Auditory Sequential Memory and Laterality Questionnaire. During the experiment, both groups were subjected to the following tasks before the drug trial, after each treatment period as well as after each wash out period: (1) A rote verbal learning task on a memory drum, (2) a dichotic listening experiment; and (3) a test of visual information processing (information absorption). (1) Subjects were presented with ten three-letter nonsense syllables, from the Glaze (1928) table of 87% Association Value, on a memory drum to be

Resultslearned to a criteria of two correct trials; (2) the dichotic listening experiment consisted of simultaneous stereophonic presentation of different high frequency monosyllable words (Thorndike, 1975) recorded on the DITMA machine at Edinburgh University; (3) The information absorption experiment consisted of six-digit random numbers presented tachistoscopically on slides from a shutter-speed controlled slide projector decreasing in speed from 2 s downwards. Subjects were given ten exposures after a 50 % threshold had been established. The subjects’ responses were analysed with an HP 2000 computer programme using the Miles and Wheeler (1977) method.

The initial battery of tests before medication revealed that the two groups, dyslexics and controls, were not significantly different for IQ on the WAIS, but several significant differences were found: The dyslexic groups were worse at digit span and coding (WAIS Subtests) (■P < 0.001); were 6 years behind on the Vernon Reading Test (P < 0.001); were 4years behind on the Schonell Spelling Test (P < 0.001); had lower Visual Sequential Memory (ITPA score) (P < 0.001); and dyslexics made more left-hand responses (P < 0.005) and were more mixed-handed (P < 0.01). The dyslexic group took almost twice as long to learn the memory drum task (P < 0.001) and made twice as many mistakes (P < 0.002). Of particular interest is immediate forgetting (this is the number of instances that a subject learns a nonsense syllable and then forgets it at the very next trial): The dyslexic group scored over three times as much as the students (P < 0.001). The information absorption experiment revealed a great difference in means [40 and 302 bits/s (Atneave, 1959)] between dyslexics and controls, respectively (P < 0.001). Moreover this latter experiment allowed us to make a fair discrimination between dyslexics and students.

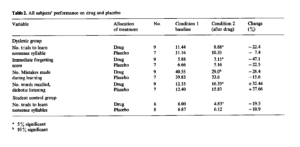

To our surprise we encountered some difficulties in the statistical analysis caused by a possible residual effect of the active compound (a learning effect could be ruled out). As our study was not designed to deal with residual effects, we commuted our analysis into a study performed on two independent samples using only the results of the first period of treatment and neglecting the results of the second period of treatment. During this first period of treatment the dyslexics showed a decrease of 22.4% in the number of trials required to reach the criteria in the rote verbal learning and the students showed a decrease of 19.6%. Both decreases are significant (P < 0.05). Under placebo conditions both dyslexics and students showed a small nonsignificant decrease in the number of trials required to reach the criteria level (Table2).

Also of great importance in the group of dyslexics was the significant decrease of immediate forgetting (P < 0.05), the number of mistakes made during learning (P < 0.10) as well as the increase of words recalled in dichotic listening (P < 0.05) (Table 2). The students did not significantly alter their immediate forgetting but they decreased their number of mistakes on both drug and placebo. Information absorption was unchanged through all conditions and groups, the dyslexics being lower throughout. Regular medical, biochemical and haematological examinations performed during the study revealed no untoward effects of the trial drug.

Discussion

The significant decrease in immediate forgetting for dyslexics is very important. This measure typifies the dyslexic learning pattern in which learning stops when an already learned item is forgotten. This halving of immediate forgetting means that the dyslexics are now able to build upon items already learned (similar to the students’ learning pattern) rather than approaching each trial as if it were the first. The students already low score (1.9) was not modified. Some individual cases went through a dramatic change due to the drug. Two dyslexic subjects halved the number of trials to learn ten nonsense syllables and also halved their immediate forgetting score. The information absorption experiment revealed great differences between dyslexics and students. It is of great interest that even when the dyslexics’ verbal learning is as high as a student group (before drug), their information absorption is very poor. This tends to show that the drug will not cure the dyslexics but act as an aid to their learning.

The administration of piracetam seems to have changed the dyslexic pattern of verbal learning to one more like that of the students’ before the drug. This gain in verbal learning and decrease in immediate forgetting would be most important in a remedial education setting. Although it is not a ‘cure’ for dyslexics (they still have great information processing problems) it is a very useful aid to learning. The group studied was an adult group who have to some extent resolved their problems with literacy. Therapeutically it would be important to establish the helpful effects of this drug on dyslexic children.

Acknowledgements. We wish to thank the following for their kind help: UCB, Pharmaceutical (Belgium); Language Development Unit, Applied Psychology Department, Aston University, Birmingham; Good Hope Hospital, Sutton Coldfield, West

109

Midlands; Ms. A. Wallis, Research Assistant; Mrs. J. Atkins; and the dyslexic and student volunteers without whom this work would not have been possible.

References

Atneave: Applications of information theory to psychology. New York: Holt 1959 Critchley, F. H.: The dyslexic child. London: Heinemann 1970 Dimond, S., Brouwers, E. Y . M.: Improvement of human memory through the use of drugs. Psychopharmacology 49. 307 -309 (1976)

Gittelman-Klein, R.: Short and long term effects ofmethyl-phenidate on cognitive performance in learning disability children. Paper given at 20th International Congress of Psychology (1972) Glaze, J.: The association value of nonsense syllables. Genet Psychol.

35,258-269 (1928)

Kirk, S., McCarthy,)., Kirk, W.: The Illinois test forpsycholinguistic abilities. University of Illinois 1969 Miles, T. R., Wheeler, J. T.: Towards a new theory of dyslexia.

Dyslexia Rev. 2, 9 11 (1974)

Orton, S. T.: Reading, writing and speech problems in children. New York: Norton 1937 Pringle Morgan, W.: A case of congenital word-blindness. Brit. Med. J. 1378 (1896)

Sciionell, F.: Graded word reading and graded word spelling tests.

Oliver and Boyd (1942)

Thomson, M. E.: Identifying the dyslexic child. Dyslexia Rev. 18. 5-12 (1977)

Thomson, M. E., Wilsher, C. R.: Practical aspects of memory.

London-New York: Academic (in press, 1979)

Thorndike, E. L.: A teacher’s word book of twenty thousand words.

New York: Gale 1975 Vernon, P. E.: The standardization of graded word reading test.

Edinburgh: Scottish Council for Research in Education 1938 Wechsler, D.: Wechsler adult intelligence scale. New York: The Psychological Corporation 1955

Received December 20, 1978