Piracetam-induced improvement of mental performance

A CONTROLLED STUDY ON NORMALLY AGING INDIVIDUALS P. Mindus, B. Cronholm, S. E. Levander and D. Schalung

A double-blind, intra-individual cross-over comparison of the mental performance of 18 aging, non-deteriorated individuals during two 4-week periods of piracetam (l-acetamide-2-pyrrolidone) and placebo administration was performed using conventional and computerized perceptual-motor tasks. In a majority of these tasks the subjects did significantly better when on piracetam than on placebo, a finding consistent with ratings completed by two independent observers. The findings indicate new avenues for the treatment of individuals with reduced mental performance possibly related to disturbed alertness — a neglected group of psychiatric conditions.

Key words: Piracetam – mental performance – aging – conventional and computerized tasks – ratings.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the mental performance of 18 normally aging, non-deteriorated subjects during 4 weeks of piracetam (1-acetamide-2-pyrrolidone, Nootropil®, UCB 6215) administration. The impairment of mental performance observed in senescence has been assumed to be related to a lowering of the level of alertness. Suboptimal levels of alertness may induce anxiety, mainly so-called “somatic anxiety” (Schalling et al. (1973, 1975)). Some aged individuals suffering from insomnia who are treated with barbiturates to lower their level of alertness may sometimes react paradoxically and develop states of confusion and anxiety. It is a common clinical observation that some of these persons benefit from caffeine, a well-known improver of alertness. Some hyperkinetic children assumed to suffer from a habitually lowered level of alertness may improve with the administration of amphetamine and related drugs (Satterfield et al. (1974)). The administration of high doses of psychostimulants to normal individuals gives rise to anxiety and subsequent decrement in performance (Claridge (1970)).

It thus appears that a too low as well as a too high level of alertness induces impairment of performance as well as certain types of anxiety. In the last 5 years pharmaceutical agents have been developed for use in patients with identifiable deviations from some “normal” performance levels, such as so-called “disorders of arousal” (for review, see Gylys & Tilson (1975)). Piracetam seems to be an interesting example of a group of substances which may improve the level of alertness when lowered without the serious side-effects of the central stimulants of today.

Previous studies on piracetam

Animal experiments indicate that piracetam exerts some protection against the effects of hypoxia and electroconvulsive stimulation (ECS) and enhances learning and memorizing (Sara & Lefevre (1972), Giurgea & Mouravieff-Lesuisse (1972)). Animal and human studies have showed no toxic or stimulant properties of the drug, which appears to act via other mechanisms than amphetamine does (Giurgea (1975)). According to Giurgea (1973), piracetam acts selectively on the telencephalon and improves the ATP/ADP ratio, which is normally decreased in aged organisms (Lehmann (1975)). A beneficial effect of piracetam on states of fatigue and decreased alertness related to aging has been described in a controlled study comprising 196 patients with an average age of 67 years (Stegink (1972)). Some authors (Macchione et al. (1974), Delwaide et al. (1975)) have been able to confirm these findings, whereas others (e.g. Gottfries (1973)) have not. In a double-blind cross-over study, piracetam counteracted the impairment of mental performance observed in patients with artificial pacemakers in whom cerebral blood circulation was influenced by decreasing the impulsive rate of their pacemakers (Lagergren & Levander (1974)). In a controlled study on retrograde dysmnesia following electroconvulsive treatment (ECT) of depressed patients, piracetam was not superior to placebo (Mindus et al. (1975)). The discrepancy between human ECT and animal ECS may be due to the administration of oxygen and muscle relaxants to patients but not to animals. Could the protective effect of piracetam in animal ECS be mainly related to a counteracting of the effects of hypoxia on memory functions?

Previous studies on piracetam and mental performance have been carried out in patients with pronounced somatic or mental disorders. The results are contradictory. It was considered of interest to study the effects of piracetam on less disabled subjects. (The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Ka-rolinska Institute.)

METHODS

Subjects

The sample was selected from a health screening program and consisted of eight male and 11 female middle-aged and older subjects with no evidence of somatic or mental disease. The program consisted of a medical examination (by A. J.-M.) and of ECG and laboratory tests. The present sample was selected from mainly white-collar employees in a company in Stockholm which offered regular medical check-ups to the employees. There were 42 subjects aged 50 years or more. The 29 subjects with no evidence of somatic and mental disease according to the medical records were selected. Twenty-three persons were invited to participate. Five refused for various reasons. The remaining 18 subjects all completed the study.

All subjects reported a slight but seemingly permanent reduction for some years in their capacity to retain or recall information. They had responded to this by for example making careful notes and working slower; by these and other compensatory actions they had been able to retain their usual positions

at work. Eight subjects were tobacco smokers. All the men and three of the women had intellectually demanding types of work and eight of the women were employees in intermediate positions.

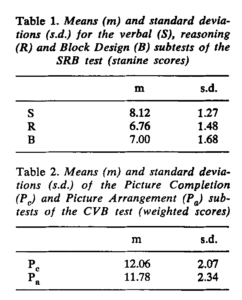

In order to exclude individuals with severe mental deterioration, the following intelligence tests were given: the SRB test, a short Swedish test consisting of a synonym and a reasoning test and the Block Design test (Dureman & Salde (1959)). In addition, Picture Completion and Picture Arrangement in the CVB Intelligence Scale (a Swedish modification of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, WAIS, Wechsler (1958)) were used. The results are given in Tables 1 and 2. The sums of the raw scores of the three SRB subtests may be expressed in IQ scores. The mean was 120.00 (s.d. ± 11.48) in the present sample. The median age of the subjects was 56 years (range 47-73).

General procedure

The subjects were given oral and written information that piracetam may have beneficial effects on certain mental functions though further studies were necessary. They were told that the piracetam content of the capsules would vary randomly and blindly. The subjects were asked to report any medication error and the intake of occasional medication other than piracetam during the study. All tests and rating scales were made familiar to the subjects prior to the study.

Medication

A single-blind placebo week for all subjects was followed by 4 weeks of placebo for half of the group and 4 weeks of piracetam for the other half double-blindly and at random. After crossing-over, those subjects starting with placebo received piracetam and those given piracetam first received placebo, both for 4 weeks. Piracetam was given three times at fixed hours at the daily dosage of 4.8 g recommended by the manufacturer. The time intervals between latest dose

and the test session were below the estimated plasma half-life time of piracetam (4.5 hours). Piracetam-containing capsules were equal to placebo in appearance and taste. Blister-packs were used and medication for only 1 week at a time was distributed.

Ratings

All rating procedures took place weekly at fixed hours. The subjects were asked to rate on an 8-point scale changes compared with the previous week in mood, vitality, concentration, memory, a global impression item and so-called somatic and psychic anxiety items (for a description of these, see Schalling et al. (1973)). The self-rating forms were developed from forms used in other research programs in our department. The psychologist rated blindly on a 4-point scale her general impression, based on her observations during the sessions, of the subject’s mood, vitality, and capacity to establish contact. Care was taken to adjust for intervening significant life events when these ratings were completed. After each 4-week period she made a psychologist medication guess, based on her observations but not on test performance. It was assumed that the period with the best impressions in these respects was a piracetam period.

After each 4-week period a semistructured, blind interview focussing on possible changes in alertness, vitality, and anxiety was made by P.M. These interviews were taped and used as a basis for a doctor medication guess similar to that described above (Lipman et al. (1965)).

Paper-and-pencil tests

The Digit Symbol Test is a code-learning test similar to that included in the WAIS (Wechsler (1958)), in which digits from 1 to 9 are paired with simple symbols. The object was to “translate” correctly as many digits as possible within a time limit of 90 seconds. Three parallel versions of the test were used. This well-known test, shown to be sensitive to drug-induced variations in cortical functioning (Townsend & Mirsky (I960)), was supplemented by the following less well-known ones.

The Bourdon-Wiersma Test. This cancellation test, which is developed from the Bourdon test, consists of a sheet of paper with 3, 4, or 5 dots forming groups. Fifty groups are arranged in 25 rows. The task was to indicate all groups with 4 dots within the time limit of 8 minutes. The number of correctly marked dot groups was scored (for a description, see Weckrot (1965)). Weckrot has found this test to be sensitive to the effects of piracetam on mental functions in states of acute alcohol withdrawal (Weckrot & Mikkonen (1972)).

The Spoke Test. This test, described by Reitan (1957), consists of circles forming the periphery of a “bicycle wheel”. In Form A the circles contain a number between 1 and 20 randomly distributed. The object was to move a finger as quickly as possible between the center of the “wheel” and the peripheral numbered circles in numerical order. In Form B the circles contain either a number as above or a letter between A and J in random order. The task was to point

to numbers and letters in alpha-numerical order. The forms were given in the AB-AB order at each session. Two parallel versions were used. The time in seconds to complete the forms was scored. The three paper-and-pencil tests were given weekly.

Computerized tests

The computerized measures were developed from perceptual-motor tasks used extensively in psychiatric and psychological research. The measures have proved to be sensitive to changes in cortical functioning induced by, for example, barbiturates and amphetamine (Idestrom & Schalling (1970)), and related to age (Suci et al. (1960), Botwinick (1973)). In the forms used here, they all have high test-retest reliabilities (Levander & Lagergren (1973)).

Two-choice Reaction Time (2RT). The reaction times to two lights were measured for 21 stimuli. The subjects responded by pressing either of two buttons corresponding to each of the lights. Stimuli were presented in random sequences in respect of position and interstimulus interval.

Critical Flicker Fusion (CFF). Using a mini-computer (LAB 8/L) on line, CFF was measured by a forced-choice interactive technique (CFF 3) and by the method of limits (CFF-ML). The CFF stimuli, consisting of three lights arranged in a triangle, were administered for 5 minutes. The flickering frequencies of successive stimuli were chosen according to the performances of the subjects. For each two correct responses the frequency was increased and for each incorrect response the frequency was decreased. In CFF-ML eight ascending (asc) and eight descending (dsc) threshold determinations were obtained.

Krakau Visual Acuity Test (KVAT). Serial visual acuity was measured using a forced choice interactive technique described elsewhere (Krakau (1967)). Successive stimuli consisting of a line with either a small upward or downward deflection were shown during 4.5 minutes. The task was to indicate the direction of the deflection by pressing corresponding buttons. Arbitrary units inversely related to the visual angle of the stimulus were scored, higher values corresponding to better performance. For a description of 2RT, CFF and KVAT, see Levander & Lager gren (1973).

Tapping. The subject’s task was to shift his/her dominant hand as fast as possible between two steel plates with a 2-cm-high obstacle in between (King (1954)). Three trials each of 6 seconds were performed for each measurement. The mean jump time was calculated.

The computerized tests were given after each 4-week period.

RESULTS

No major medication error or occasional intake of other drugs likely to exert large influence on the results were reported. No side-effects were noted.

Ratings

In the self-ratings there were no significant differences between piracetam and placebo in any of the seven variables used. The medication guesses performed by the psychologist were correct in respect of placebo-piracetam order in 12 of the 18 subjects, which, on a 5 % level (Fisher Exact Probability Test), are significantly more instances than expected by chance. The doctor medication guesses were correct in 11 out of 16 subjects, which is also significant on a 5 % level (in two subjects the 4-week periods were too similar to permit discrimination). There was agreement between the psychologist’s and the doctor’s medication guesses in 9 out of 16 subjects.

Paper-and-pencil tests

All data from these and from the computerized tests were subjected to analyses of variance, repeated measures design. Since previous studies on piracetam using these tests had yielded positive results, the use of one-tailed tests seemed justifiable except for the ratings which had not been used in their present form.

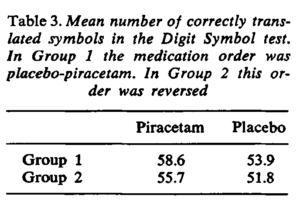

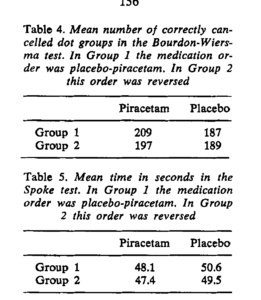

The Digit Symbol Test. The mean numbers of correct responses in the two groups of subjects during piracetam and placebo administration are given in Table 3. There was a highly significant difference in performance in favor of piracetam (F(l,16) = 18.94; P < 0.001).

The Bourdon-Wiersma Test. The mean numbers of correctly indicated 4-dot groups in the two groups of subjects under piracetam and placebo conditions are given in Table 4. There was a highly significant positive effect of piracetam on performance (F(l,16) = 19.53; P < 0.001). There was no significant trend within any 4-week period.

The Spoke Test. The mean times taken to perform the task during piracetam and placebo administration are given in Table 5. The time was significantly shorter during piracetam administration (F(l,16) = 5.21; P < 0.05).

Except for the expected significant training effects in the three paper-and-pencil tests, no significant trends within any 4-week period was observed in any one of the tests. This may be interpreted to imply that the effect of piracetam was obtained already within the 1st week of treatment.

Computerized tests

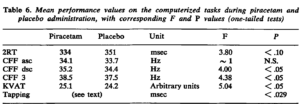

The mean performance values during piracetam and placebo administration are given in Table 6. Subjects performed significantly better when on piracetam than on placebo on CFF dsc, CFF 3, KVAT and almost significantly better on 2RT. There was a positive trend in CFF asc, but it did not reach the level of significance. As regards tapping, one of the subjects had a very pronounced increased jump time during piracetam administration but there was no decrease in performance in the other tests. Inspection of the plottings suggested that this individual had received a very high weight in the analysis. The lack of homogeneity of variance thus made analysis of variance an unsuitable procedure. Using a non-parametric sign test on the number of subjects with increased versus decreased tapping performance during piracetam and placebo administration, the probability of obtaining the present distribution due to chance was 0.029 (one-tailed), indicating a significantly better performance also on tapping with piracetam administration.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies on piracetam and mental performance have been performed on individuals with some degree of pathology. Since the results are contradictory, it was regarded as of interest to study a group of normally aging individuals with no evidence of disease. Subjects engaged in intellectually demanding types of work are assumed to be sensitive to changes in their mental function and highly motivated to participate in a study of this kind. Thus, the sample was regarded as suitable for the purpose of the study.

The results of the present study indicate that the mental functioning of the subjects was better when on piracetam than on placebo in most of the tests used. Results in the same direction were obtained in the self-ratings although

the level of significance was not reached. In order to reduce effects of expectation, subjects were kept ignorant not only of the contents of capsules but also of the duration of placebo and piracetam administration periods. When the study was accomplished, subjects were asked whether they wanted to continue taking piracetam or not. Only one subject declined to do so. To some extent this positive attitude to the drug on the part of most subjects may represent a placebo effect. It is possible that their attitudes were based to some extent also on pharmacological effects.

As for the question of why no improvements were detected in the self-ratings, this may at first glance be considered as a serious drawback to the clinical usefulness of the drug. It is obvious, however, that the reliability of the self-ratings is not high. When completing the self-rating forms for reporting changes in alertness, vitality, and other items, the subjects often complained of difficulties in assigning any such change to the points in the scale. This may be related to the scale used. Moreover, it may be a hard task to estimate changes in these respects compared with the previous week, since the conditions may not be recalled distinctly or may easily be confounded with one’s habitual state. Also, noting changes in one’s mental state over periods of time while living a normal, active life influenced by various “life changes” may be difficult. A simpler scale with only a few rough points might have been more appropriate. Since most subjects could provide the two observers with valid information for a piracetam-placebo discrimination, it appears that a certain subjective improvement had taken place, even though this was not revealed in the self-ratings.

There was a disagreement between the two observers in medication guesses in some subjects. This is not astonishing since the medication guesses were based on different sets of observations obtained at different occasions and valid for different time spans. Furthermore, the observers had different clinical experience and may have been differentially sensitive to the cues given.

The observers’ ratings were in line with all the paper-and-pencil tasks and a majority of the computerized ones. Since the performance in this type of task has been shown to reflect the level of cortical functioning (Townsend & Mirsky (1960), Idestrom & Schalling (1970)), the findings may at least partly be due to improvements in cortical functioning related to piracetam administration.

One may speculate about how piracetam achieves this improvement: are our

results due to improved functions of somewhat deteriorated cells in the CNS, to a compensatory enhancement of the functioning of (still) non-deteriorated cells, or a combination of both? In their study on pace-maker patients, Lager-gren & Levander (1974) interpreted the findings to imply that piracetam had exerted some protection against the bradycardia-induced cerebral hypoxia. But in one of the measures, the KVAT, performance was better when the patients were on piracetam, irrespective of the heart rate. This finding indicates that also the age-related decrement in performance may have been counteracted by piracetam (the median age of the pace-maker patients was 70 years). However, the drug appears to improve performance on some tasks also in young subjects. Dimond (1975) in a recent study, administered piracetam to 16 young healthy students. By performing a double-blind interindividual comparison he noted significant improvements of direct and delayed recall following verbal learning. If other authors can confirm Dimond’s findings this would support the assumption that an improvement in the functions of non-deteriorated cells may be induced by piracetam. It seems that there is little likelihood that the drug has noticeable beneficial effects on severely deteriorated cells (Macchione et al. (1974)). An influence of piracetam on non-deteriorated and only moderately deteriorated cells is perhaps the most plausible. More data are certainly needed before an assessment of the mode of action of the drug may be made.

CONCLUSION

The results in this study point to a beneficial effect of piracetam on mental performance in aging, non-deteriorated subjects. It must be emphasized that although the effects were statistically significant, the size of the effects in each individual case was moderate. However, the hazards of more potent agents, such as amphetamine, form obstacles to their clinical use. Other therapeutic avenues must be found for middle-aged individuals handicapped by early psychological aging and for patients with impaired mental performance due to trauma, age, or a habitually lowered level of alertness as may be the case in some hyperkinetic children (see Satterfield et al. (1974)). We agree with Lehmann’s (1975) conclusion that: “its [piracetam’s] selective action on telencephalic structures and absence of toxicity and side-effects make it an extremely interesting representative of this new nootropic – “mindacting” – class of psychoactive agents.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grants to B. Cronholm and D. Schalling, and to S. E. Levander from the Swedish Medical Research Council (21X-3473 and 26P-3588), from Loo and Hans Osterman’s Fund for Medical Research and from UCB Nordiska AB to P. Mindus. Agneta lacobson-Mindus, M.D., kindly gave us access to the medical records. Vila Bjerneld, psychologist, gave the tests and rated the subjects.

This is a revised and enlarged version of a paper read at the 1975 annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

REFERENCES

Botwinick, 1. (1973): Aging and behaviour. Springer, New York.

Claridge, G. (1970): Drugs and human behaviour. Allen Lane, The Penguin Press, London.

Delwaide,P.H., M.Ylieff, A. M.Gyselinck-Mambourg, L.Dijeux <6 A.Hurlet (1975): Effets du piracetam sur la demence senile. In Agnoli, A. (ed.): Proceedings of “Nooanaleptic and nootropic drugs”, Rome, Sept. 17, pp. 197-110.

Dimond,S.J. (1975): Drugs to improve learning performance and verbal registration in man. In Agnoli, A. (ed.): Proceedings of “Nooanaleptic and nootropic drugs”, Rome, Sept. 17, pp. 107-110.

Dureman, /., & H. Sdlde (1959): Psychometric and experimental methods for the clinical evaluation of mental functioning. Almquist & Wiksell, Stockholm.

Giurgea, C. E. (1973): The “nootropic” approach to the integrative activity of the brain. Condition. Reflex 8, 108-115.

Giurgea, C. E. (1975): Personal communication.

Giurgea, C. E., & F. Mouravieff-Lesuisse (1972): Effet facilitates du piracetam sur un apprentissage repetitif chez le rat. J. Pharmacol. 3, 17-30.

Gottfries, C.-G. (1973): Personal communication.

Gylys,J.A., A. H. A.Tilson (1975): Pharmacological approaches to maintaining and improving waking functions. In: Annual reports in medicinal chemistry, Vol. 10. Academic Press, New York, pp. 21-29.

Idestrom, C.-M., & D. Schalling (1970): Objective effects of dexamphetamine and amobarbital and their relations to psychasthenic personality traits. Psychopharma-cologia (Berl.) 17, 399-413.

King,H.E. (1954): Psychomotor aspects of mental disease. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Krakau, C. E. T. (1967): An autonomic apparatus for time series analysis of visual acuity. Vision Res. 7, 99-105.

Lagergren, K., & S.E.Levander (1974): A double-blind study on the effects of piracetam upon perceptual and psychomotor performance at varied heart rates. Psychopharmacologia (Berl.) 39, 97-104.

Lehmann, H. E. (1975): Rational pharmacotherapy in geropsychiatry. Paper read at the 10th International Congress of Gerontology, Jerusalem.

Levander, S. E., & K. Lagergren (1973): Four vigilance indicators for use with a minicomputer. Rep. Psychol. Lab., University of Stockholm, No. 381.

Lipman, R. S., O. C. lonathon, L. C. Park & K. Pickets (1965): Sensitivity of symptom and nonsymptom-focussed criteria of outpatient drug efficacy. Amer. J. Psychiat. 122, 24-27.

Macchione, C., M. Molaschi, F. Fabris & F. S. Feruglio (1974): Results with piracetam in the management of senile psychoorganic syndromes in 182 subjects. Paper read at the VII European Congress of Gerontology, Manchester, England.

Mindus, P., B. Cronholm & S. E. Levander (1975): Does piracetam counteract the ECT-induced memory dysfunction in depressed patients? Acta psychiat. scand. 51, 319-326.

Reitan,R.M. (1957): The comparative effects of placebo, ultram and meprobamate on psychological test performances. Antibiot. Med. 4, 158-164.

Sara, S. I., & D. Lefevre (1972): Hypoxia-induced amnesia in one-trial learning and pharmacological protection by piracetam. Psychopharmacologia (Berl.) 25, 32-40.

Satterfield, J. H., D. P. Cantwell & B. T. Satterfield (1974): Pathophysiology of the hyperactive child syndrome. Arch. gen. Psychiat. 31, 831-844.

Schalling, D., B. Cronholm & M. Asberg (1975): Components of state and trait anxiety as related to personality and arousal. In Levi, L. (ed.): Emotions: Their parameters and measurement. Raven Press, New York, pp. 603-617.

Schalling, D., B. Cronholm, M. Asberg & S. Espmark (1973): Ratings of psychic and somatic anxiety indicants. Acta psychiat. scand. 49, 353-368.

Stegink,A.J. (1972): The clinical use of piracetam, a new nootropic drug. Drug Res. 22, 975-977.

Suci, G. !., M. D. Davidoff & W. W. Survillo (1960): Reaction time as a function of stimulus information and age. J. exp. Psychol. 60, 242-244.

Townsend, A. M., & A.F.Mirsky (1960): A comparison of the effects of meprobamate, phenobarbital and d-amphetamine on two psychological tests. J. nerv. ment. Dis. 130, 212-216.

Wechsler, D. (1958): The measurement and appraisal of adult intelligence. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore.

Weckrot, J. (1965): On the relationship between severity of brain injury and the level and structure of intellectual performance. Jyvaskyla studies in education, psychology and social research 12. Cited in: Weckrot <6 Mikkonen (1972).

Weckrot,!., & H.Mikkonen (1972): On the effect of UCB 6215 in certain intellectual perceptual and psychomotor performance traits and traits of subjectively rated mental state. Manuscript UCB, Brussels.

Received April 12, 1976 Per Mindus, M.D.

Department of Psychiatry The Karolinska Institute S-104 01 Stockholm 60 Sweden